Replay and Rest: The Cost of Rest

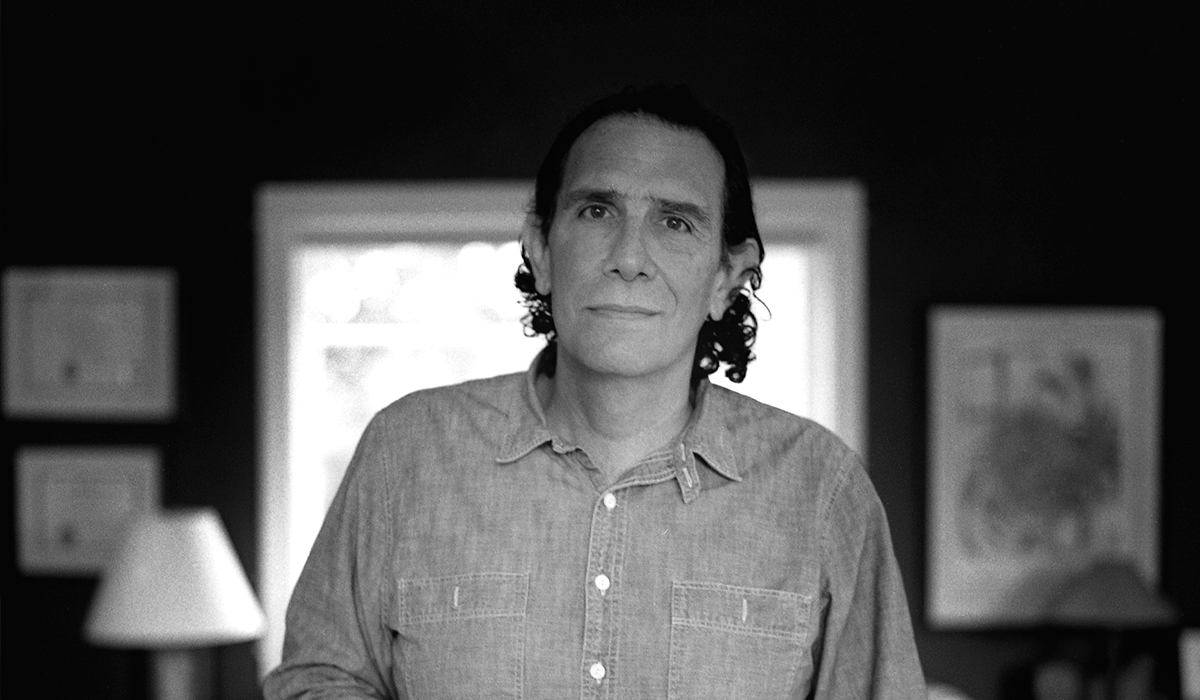

The second episode in our “Replay and Rest” series is a reflection from Dr. Dan Allender during his sabbatical from teaching back in 2015. We hope that listening back to this portion of Dan’s story will serve as an encouragement to examine our own attitudes towards rest.

We know that rest is of the utmost importance in order to recover from the toll that stress takes on our bodies, our minds, and our hearts. Here at The Allender Center, we are practicing what we teach and many of our team members are taking reduced work hours and vacation time during the month of July. In that spirit, we are choosing to re-air three popular past episodes that center around the theme of rest this month. Even if you have heard these before, we hope that you will take the time to listen, reflect, and purposely make space for rest in your own life.

Episode Transcript:

Dan: I thought I would step us back into reflecting on Sabbath and using my own sabbatical as a context to invite you, to ponder some of the implications of, your own approach to rest, to play, to delight, to reprise bit of what I put words to the last time, we are meant, for a weekly. Now that… What’s the next word. Weekly rest, yes, it’s what God did on the seventh day, but rest, as we mostly think of it is taking a break.

I’m so sad to say that I think many people take a break, uh, by watching a film, watching movies, watching TV, just saw a report and have no means to confirm, or offer you where it’s from. But it suggested that we look at our iPhones or our smartphones somewhere around 240 times a day, and that we are in the presence of a screen, not TV, but a screen 3.5 hours a day. Now, if you add, the absolutely overwhelming statistic that the average American watches 4.6 hours of TV a day, we are vicarious watchers of other people’s life, joy, suffering, shame, and struggle. And it doesn’t really imply that we’re living much of a life according to the way that God designed.

But the issue is first and foremost, that we need to say that resting, is not lounging. It’s not vegetating. Vegging out. It’s not tuning out. Um, it’s an engagement with what the heart desires that deeply leads into a kind of exploration that brings a taste of wonder and goodness, and therefore opens the heart to receive and to offer delight. If that’s what a day, a unique day weekly is meant to be, then the privilege I have I think is, almost incomprehensible and that is I get a year to be on sabbatical.

Now, if my wife were listening, and able to speak at this juncture she’d say you better clarify. You’re still traveling, almost 20 weekends on behalf of the school. You’ve got clients that you see. You’re writing, finishing a book on The Wounded Heart, 2.0, a 25 year retrospective of the work that you did on The Wounded Heart. And honestly, my wife, who’s a phenomenally kind generous but also articulate and honest woman would kind of be screaming, this is not what most people think of with the word sabbatical.

Well, the fact is, I am not traveling from my home, to the school that I love and teach at, each Monday and Tuesday. And as a result, I have more time. I have more down time, more time, not commuting, more time, not thinking about classes more time, not grading. It isn’t even the amount of hours, it’s that for a season, I’m able to turn my face from one world to then be turning it to another. And that’s the complication. My goodness. That’s the complication that comes for any of us who are privileged with a sabbatical, but even every one of us, that’s given the gift of a weekly Sabbath. What do you want to do with your one utterly free incomprehensibly good day, or in this case a full year?

Well, one of the effects, for me, and you may note it in my voice, I’m not well, um, I’m certainly better than I was yesterday and way better than two days and three days ago. I have nothing worse at the moment, than, oh, I just don’t like the phrase, the common cold, but, it is, chest intrusive, snot filled, dripping, coughing, energy depriving brains sluggish, in a way that, uh, I don’t know how wise it is to be making this when I’m admitting, that I’m not fully well, but the fact is, if you were to look at my history, and my wife has been gracious enough to provide me with the data when I have not wanted to see it, when December comes given that I’ve been in academic since, approximately 1978, I tend to push very hard through the fall. I get to December, usually I have grading, end of semester activities and somewhere between the 12th and 23rd or 4th of December I will get a cold, the number of times that cold tragically is moved into bronchitis, pneumonia, way more times than I can count on both hands.

So, it is not uncommon for me to get ill in December, spend a good portion of this so called academic break, sleeping, restoring, and then, returning in January not fully well, but able enough to continue and then that sets up the high probability somewhere early February, mid-February, a second cold, because my immune system is frazzled, worn down to a pulp and somehow it takes a few days, you know, this scenario, I’m not gonna continue somehow we get to spring and health is restored, but it does seem like months of my normal life, are taken down in large measure because I’ve expended an enormous amount of the word we normally use is energy. Good word, accurate word, but another word to be implied to that is the word cortisol.

I’ve, I’ve used a great deal of cortisol pumping through my body. And cortisol is a pumps through your body in many ways is the same phenomena, of fight or flight. It’s what energizes us to change the process of how our body metabolizes food, how we metabolize sleep, and anyone, who’s stepping into a fairly high paced, complicated, stressed life. Like you have children, already you live what I just put words to. You have a pretty complex job, even more so, you’ve got, infringing or difficult relationships that are about you. I hope you can hear a simple phrase. You are under high stress and your body has learned to regulate that stress as a whole new norm, so that you are pumping way more cortisol than what is actually necessary, in a real fight/flight situation, but your body doesn’t know that. So as a consequence, put in very generalized terms, what happens when high levels of cortisol are pumping. Your body begins to say, wow, we’re in a real fight or flight. Survival is crucial. So we’re gonna put aside, all sorts of other realities that might take your focus, your time, your energy. We’re not going to be metabolizing muscle mass. We’re actually going to be taking, the enzymes, are going to basically take the amino acids and focus on creating more energy. So it is a literal sense in which under high-stress we deplete; we are eating our body’s strength to continue the high level of activity, that we have come to view as just a normal life. Well, the complication of course, is that one of the effects of this is that we’re using all sorts, of red blood cells, to pump energy and our immune system that depends on our blood supply is being focused away from being able to really, shall we say, deal with the interior problem of our own disease process.

So I’m putting it, in a very third grade level, but let’s just say the nature of stress, is that it depletes and eats and focuses our defense structures on the outside leaving in many ways where we live in the castle of our body, mostly unprotected. And as a result, we are going to be vastly more susceptible, not just to minor illnesses, like a cold but our whole body structure, has been, um, immunologically, deprived in a way in which, it is almost without question in our day, that a lot of disease processes come from trauma that we have addressed through our own fight and flight through the use of cortisol, defending ourselves by our own activities and then 10, 20, 30 years later, our bodies are a wreck. You know, if you wanna do more reading and thinking about this, that goes beyond, my third grade level of reflection, two books I’d recommend at this juncture. One is called Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. It’s by Robert Saplosky S A P O L S K Y, and a book entitled The Cortisol Connection, by Sean Talbott, T A L B O T T. They’re both dense books. They’re not, overnight reads, both are excellent, really excellent writers, and take, some pretty arcane neurophysiological processes, brain processes, into a very communicable, reading, for anybody willing to sort of slog through. That’s a new word. That’s a new concept, understanding something about enzymes and neurotransmitters and inner structures of the brain. It’s a very, I mean, both are very, very helpful books, but if we can get to, again, the point, it is that your body’s susceptibility to illness can be postponed by keeping up stress. And that is the dark potential for a man like me that loves what I get to do.

I mean, I love my job. I hardly even think, it fits the word to call it a job. And I love the drama, of being able to step into the work of God in an individual’s life or in a class’s life or a small group’s life, and the sense of uncertainty and danger, and spiritual warfare, the complexity of the privilege I get, to be involved in the work of redemption. I mean, part of me goes, it’s a candy store for a person like me who loves sugar. And so when I named that I’d been working, I worked at my father’s bakery, I think, as I was around age nine. And really one of the major gifts that I received from my father was his work ethic. And I remember him saying, it’s not exactly complimentary, but he goes, you may not be very bright. And certainly the evidence at that time in my life, would’ve been that I wasn’t too bright. he said, you’re, you know, you’re not gonna have the ability to sort of depend on being smart, but you can always outwork those work, those who put their brains first. And so the story of the tortoise and the hare. I don’t know when I heard that story, but I kind of knew that I was way more like the tortoise at least from my father’s opinion, than I was the hare. And so I can look over countless areas of my life, where I’ve just plotted, and somehow stumbled forward.

And then, certainly it was a number of years ago, we were, my wife and I were visiting with a dear friend in Chiang Mai, Thailand. And we are sitting around for a day, just leisurely day, literally a day where we’re just probably not gonna leave the living room and kitchen. And the two of them began talking about me. And I could hear because I was, you know, doing a little writing, but I wasn’t really paying attention, but they started laughing and laughing hard. It was hard to not turn my attention. And both of them said, we didn’t do this on purpose, but we’re sort of curious how long you could have lasted, doing what you were doing when we’re talking about you very clearly over the last 20, 30 minutes. The issue there was, well, as my good friend, a psychologist said, you’ve got ADD. It’s like, no, I don’t. I have many pathologies, much brokenness, but no, I don’t think so. So, she said, I don’t think you’ve worked with kids long enough to actually be clear, that you’ve got a bit of hyperfocus ADD. And so we got online, I took a small little test and low and behold.

Do you hear the drama? I love what I do. I get great joy. A privilege of being part of people’s lives feels keener to me than the idea of being alive. And I work hard. I love to work. I can focus for 8 to 10 hours on a book, a topic, a thought a person and the time breathes away similarly to what it’s like for me to be on a river and fly fishing. So I made to work, and then my wife, brilliantly decades ago has kept up this question of what are you gonna do with the Sabbath? And my response wickedly has been often, I”m a forgiven Sabbath breaker. I’m a breaker. I break the Sabbath, I break the fourth commandment. And again, underscore it’s the fourth commandment. It’s not an option. It’s not something that’s to be taken lightly, but I look at my life and I do worse than take it lightly. I know full well how important it is, but I always seem to have some amazing this week, this month, this year justification.

So as we enter into really the first four weeks, five weeks, of our sabbatical, I’m looking at, about eight or nine days in which I had the flu. Now I’m on my fifth day, of restoration from a cold. So about a third, maybe quarter of the days of our sabbatical I’ve spent recovering from illness. Really the question that has to be addressed that will somehow move toward in our next conversation is what are we so afraid of in slowing down? Why do we need noise? Why do we need to almost chronically look at our phone to see if there’s a text or a message a voicemail? Why is there this sense that if we stop slow down, things are going to get worse.

And something of the conclusion, of what I’m saying, is that at least in my case, if I slow down, as I have to some degree over these last five weeks, my body is going to take the opportunity, to begin to restore. But in that it comes painfully through illness, oftentimes, a person like me will rest only when, I’ve been forced to do so and illness is not an excuse. I’m not justifying, that this be, my primary way of entering into Shabbat. But it is a heartbreak to name, I’ve had to rest. I’ve had to get 8 to 10 hours sleep, each night, the last few days, I’ve not been able to press on to accomplish, the finishing of a workbook related to The Wounded Heart 2.0. There are things that are going to go by the wayside. So can we bear that slowing down creates its own chaos, actually for most of us, for at least a short season, and maybe longer than we wish, that it actually will get worse.

Can we begin to name that we’re operating at a normal high level of stress that our bodies are really going to break down, and that if we don’t somewhere in our thirties, forties, fifties, sixties, begin to care for our body. We’re doing more than burning out. We are lighting, our very soul and body on fire in a way in which it’s an immolation, a self destruction, a martyrdom that bears nothing of what it means to know the delight of God.