Scarcity

The orphan, widow, or stranger who lives in scarcity is often scrappy. She binds her wounds of betrayal, powerlessness, and loneliness with her vigilance, wit, ingenuity, and distrust. She’s a bit of a street rat. She knows how to make do with bits and pieces. Her skills and abilities can lead us to marvel at her seeming resiliency. I am this scrapper. I would invite you to consider whether you might be one as well.

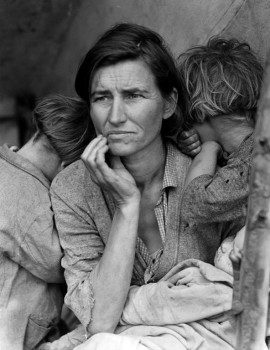

Scarcity is often a descriptor we designate for the developing world. We assume that it  warrants the imagery of physical poverty. The photojournalist Dorothea Lange captured this understanding of scarcity in her celebrated photograph “Migrant Mother”—an image taken during the Dust Bowl depicting the harsh life of a family living in squalor, filth, and financial demise. In a similar vein, National Geographic invited us to grieve the Ethiopian famine of 1984 when they exposed the scenes of malnourished children whose protruding bellies scream of starvation and deprivation. Because of these extreme and unimaginable horrors, we often assign scarcity to those across oceans or to particularly “rough” neighborhoods in our American cities. We minimize our own experience of scarcity because we compare our middle class lives against the backdrop of today’s Syrian refugees and those dying of Ebola in West Africa.

warrants the imagery of physical poverty. The photojournalist Dorothea Lange captured this understanding of scarcity in her celebrated photograph “Migrant Mother”—an image taken during the Dust Bowl depicting the harsh life of a family living in squalor, filth, and financial demise. In a similar vein, National Geographic invited us to grieve the Ethiopian famine of 1984 when they exposed the scenes of malnourished children whose protruding bellies scream of starvation and deprivation. Because of these extreme and unimaginable horrors, we often assign scarcity to those across oceans or to particularly “rough” neighborhoods in our American cities. We minimize our own experience of scarcity because we compare our middle class lives against the backdrop of today’s Syrian refugees and those dying of Ebola in West Africa.

Webster’s dictionary invites us to read and pronounce scarcity as follows: scar – ci – ty. Webster defines it as “the state of being in short supply, especially want of provisions for the support of life.” Dearth, lack, insufficiency, paucity, meagerness, and poverty are Webster’s synonyms offered to paint a more accurate picture. Upon quick glance or slow, deliberate pronunciation, scarcity could be read as SCAR CITY. Is this not a more accurate read?

Scar City, or the City of Scars, is a place of neglect. The City of Scars is the land where we live without, where we bear a kind of vulnerability that leaves us naked, wanting, longing, and seemingly unprotected. It is a desolate place, a desert, a no man’s land. It’s where we live in desperation. It’s where we spar for power, property, sustenance. It’s where we live in fear of loss, thievery, and devastation. It’s a place where there is never enough.

I write as a woman who has known the reality of two different kinds of scarcity. The first fits the picture previously mentioned, the assumed description of scarcity, and I will only linger there so as to marry it to another kind of devastation. I have lived in one of the City of Scars, a village in East Africa that has known war, poverty, and disease. Here, the “plight” of scarcity was far more than a battle around infrequent or inconsistent access to clean water, electricity, medicine, or food. It was more than the appeal for young girls to wed older, polygamous men to escape the life of want and need. It was more than orphans made from AIDS and civil unrest. What was particularly heartbreaking, possibly beyond all the aforementioned realities, was the plague that infects the soul and relationships of those in the City of Scars. Scarcity bred suspicion. It created fear and cynicism. It pitted friends and family against one another. In this city I found myself questioning the generosity and goodness of others, when I am one typically prone to openness and trust. I became dis-eased.

Yet, this dis-ease was not foreign to me; it was merely the first time I experienced it in connection to the physical. The dis-ease of scarcity is one I have known from an orphaned heart. I have lived in terror that I will be alone and left in a position of needing to rely solely upon myself. I have lived believing that my greatest need for love and companionship will go unmet. I have known a kind of neglect that has left me resource guarding and in a vow of self-sufficiency. Out of the position of scarcity, I have also become prideful and even arrogant in my ability to survive in meagerness and make do with scraps.

The danger of scarcity is the applause its victims receive for their resilience, resourcefulness, and independence. Those who “pull themselves up by the bootstraps” are considered heroic. But there is a cost when these traits are wedded to the fierce promise, the vow, that I alone will take care of myself. This vow is made in the deeply entrenched belief that no one else will provide, particularly God.

I invite you to consider your narratives that leave you living in Scar City. I invite you to consider the lands where you have dwelled in want and longing. Only then can we begin to examine the audacious promise of abundance.