You Can Go Home

Today, Becky Allender writes about the 45th high school reunion she and Dan Allender, her husband, recently attended. Dan offered some pre-reflections about the reunion on a recent podcast, and he’ll share more about his experience on this week’s episode. Here, Becky writes about how the reunion is an opportunity to remember both the beauty and the turmoil of the past—ultimately, a reminder that death does not have the last word. This post originally appeared on Red Tent Living.

Thomas Wolfe wrote a novel entitled You Can’t Go Home Again. But indeed, you can. It was our 45th high school reunion and, as usual, I had to encourage my husband to go. “It’s a good time to combine seeing family and friends,” I said. But, as always, it took some convincing. Because even though we went to the same high school, we had completely different experiences. For me, high school was like a magic carpet whisking me away from the turmoil of my mother.

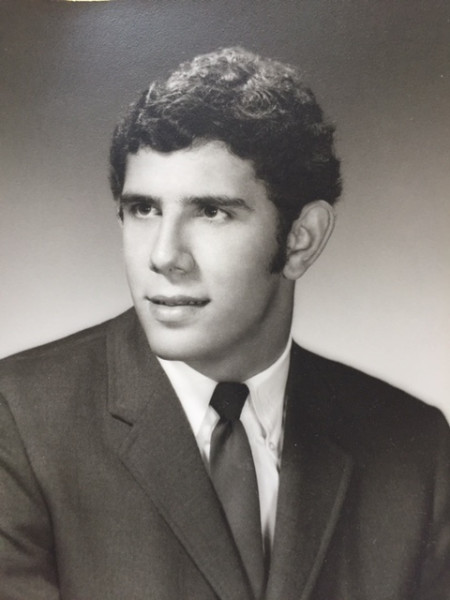

Dan had already escaped his family by nearly moving in with his best friend, Tremper Longman. He played football and was known as a badass who shouldn’t be crossed without dire consequences. I was friendly with almost everyone and was able to cross between multiple cliques. So I anticipate returning and can’t quite fathom why my husband is reluctant. He knows I’ll go without him, and that usually incites him, begrudgingly, to come.

Dan had already escaped his family by nearly moving in with his best friend, Tremper Longman. He played football and was known as a badass who shouldn’t be crossed without dire consequences. I was friendly with almost everyone and was able to cross between multiple cliques. So I anticipate returning and can’t quite fathom why my husband is reluctant. He knows I’ll go without him, and that usually incites him, begrudgingly, to come.

The tradition at our high school is a class reunion every five years on the Fourth of July. I think I have gone to all but three reunions. The question asked is, “Why? Why would you want to return every five years?” It may sound too severe, but I go back for the same reason veterans return to be with their comrades long after the war is over. High school was easier for me than my husband, but it was also a war zone. Veterans return to remember and be reminded that life wins—death doesn’t have the final word.

The wounds and scars of high school are usually hidden during that time and for at least 20 years after. It appears we need to be decades from the turmoil to begin to account for all that was suffered. The popular girls weren’t that confident. The jocks were wondering if they had already hit their peak. The tech geeks didn’t realize they would one day rule the world. None of us had a clue what we had been through or what was truly ahead. But the future opened before us like a Montana sky—vast, huge, beautiful, and ominous.

I return because my future is far briefer than my past. I don’t go back to suckle at the teat of nostalgia. Nostalgia is a rewriting of the past to enable us to whistle in the dark as we get closer to death. I go back to prepare my heart for the inevitable beauty and suffering of the future. The best way to lean into the future is to bless and honor the gift of the past.

When I am with Paula I remember the “young Becky” of second grade who moved to a new neighborhood. I remember Paula’s kindness and her tenderly holding my new puppy, Pixie. I remember her parents, her home, her mother and mine leading our Blue Bird troop in her basement. I remember transferring to my new elementary school after Easter weekend. I remember being scared to death riding in my father’s Volkswagen to the parking lot to be escorted to Miss Myers’ second grade class. I remember Sara Smith being assigned to me for the week to see that I got to all the places I needed to go. I remember the smell of the cafeteria and Dessy, the overweight, beautiful cook, with silver braids that wrapped around the crown of her head, and Kirby, the rotund, gray-haired custodian who always greeted me and made sure everyone had a four-cent milk carton at lunch. I loved elementary school.

Junior high school becomes sketchier, with traumatic memories of Cotillion dinner dances, school dances, algebra, biology, study halls, the large, looming cafeteria, and no recesses. A few times I got off the school bus before my stop and walked to my elementary school to visit my fifth and sixth grade teachers. I longed to be back in Windermere, where life seemed simpler and kinder. Junior high, with lockers and changing classrooms each period (not to mention getting your period), made life less secure and more uncertain. After three years we couldn’t wait to leave Hastings.

High school brought football games, school musicals, report cards, mid-terms, finals, boyfriends, and school dances. Most of my friends were part of carpools of five with a parent driving one of the days of the week. When we got our licenses, we usually got one of the family cars one day a week to drive the carpool to school. As girls, before Title Nine, we almost always came home after school.

January of our senior year, our dress code changed and we could wear pants to school. Along with pants and miniskirts and marijuana, our rage against the Vietnam War grew stronger and our world seemed crazier with assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. We were ready to leave the halls of our high school and break away. We had lived through the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Bay of Pigs, John F. Kennedy’s assassination and four students killed on the Kent State campus not too far way. Life seemed to be out of control, and by the time we graduated we were ready to leave.

And leave we did!

Yet, our class, our friends, have stayed connected. Cliques have faded and friendships have swayed past lines that once were rigid. At this stage of life there is little boasting. Careers, accomplishments, and wealth are not entities that separate us. We’ve lost forty classmates, and many are currently fighting life-threatening battles.

We’ve weathered losing parents, children, siblings, and marriages. We’ve become a class where “class” does not matter. When I see my friends from the class of ‘70, I see the spirit of Barb or the spirit of Judy. They are not 63 year-olds to me. They are the ones I knew at a younger time.

They knew my potential goodness; they intuitively understood my brokenness and wounds from my family (and if they didn’t then, they do now). They know how I suffered and how I was blessed. It helps me remember who I am, where I came from, and where I am headed. It is this deep connection and the sinews of friendship that allow me to see that, though death is inevitable, it never has the final word.