Taking My Place

What does it mean to be made in the image of a triune God, a God who is marked by intimacy and mutuality at the very core? Here, Becky Allender writes about how the dance of the Trinity has invited her to become more truly herself, both fully independent and intimately connected to those she loves, and to take her place in the dance. This post originally appeared on Red Tent Living.

We arrived a bit late for dinner at the Naples Ritz-Carlton ballroom for a Serge Missions Fundraiser. We were disheveled after a day of travel from Seattle, and it felt strange to be in a silk summer dress in November when a few minutes before I had been wearing jeans, a sweater, and boots. Our name tags instructed us to sit at table number eight, and when we got there two women at our table greeted us and said that they felt like they knew me and then said, “Hi, Dan, it’s nice to meet you too, but we really like your wife’s writing.” I have traveled with my husband for four decades and been the invisible spouse who loves what he teaches but am often unnoticed. This greeting was completely unexpected, and I heard Dan laugh as he delighted in this new chapter of our lives.

I have honed this black op art of invisibility from an early age. My parents were part of “The Greatest Generation,” Tom Brokaw’s coined phrase for those who survived the Great Depression and World War II. With youthful exuberance my parents gave their time to countless groups helping orphaned boys, raising money for college scholarships for girls, funding a new wing at the art museum, building a church, and so on. I was to be a good girl—proof of their hard work and good character. I was never to dispute or contradict their opinion or desire. I was to be seen and not heard.

I have honed this black op art of invisibility from an early age.

It was wise to stay out of their way because they had so much to do. Being quiet and out of sight was a safe haven and wise choice. Being the middle child allowed me to hone this skill even more. I took those skills into my marriage. Further, I married a man whose presence is large and fills a room even when he is quiet. When I attended his conferences or when he preached, there was little curiosity about me. And usually I was okay with that.

The dance of invisibility happened especially when I traveled with my husband. I did not feel invisible at home. I rarely traveled with Dan because my life was full having babies, raising children, and holding down the fort. When the nest was empty is when new troubles began, and our even-keeled marriage became choppy in uncharted stormy waters.

I felt jealous of his skillful teaching and envious of the participants and their aliveness and pursuit of Dan. I became critical of his words and the judge of the accuracy of dates and concepts related to the stories he told about our lives and family. I knew it was my issue to sort out, but it wasn’t clear what would relieve the pain of feeling left out like the dinghy being pulled behind the yacht.

The empty nest was a season of inquiry and a quest for position. Who was I to be in this third phase of our marriage? My desires tossed me up and down and I felt mean or misunderstood. The way forward didn’t have a clear compass point, and the “new” was a bit like Alice’s Wonderland. Sometimes I was too big and noisy, and other times my smallness was a haven of peace or a prison of despair. I ventured to new places and I boarded up old doors. I paved new paths to others and I fenced in areas of my heart for healing.

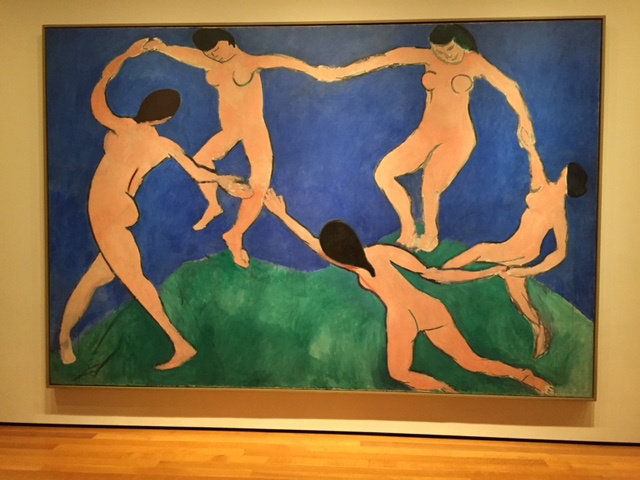

It felt like I was spinning in a dangerous dance. I happened on the theological idea of perichoresis. Perichoresis is the Greek word for rotation or dance and in early church theology it became a way to talk about the interplay of the members of the Trinity. The Trinity dances together in a holy mutual indwelling without loss of identity. I love to imagine each person of the Trinity, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit voluntarily circling the other two and dancing with joy and love for one another.

But it involves us too, because we have been resurrected with Christ in his ascension and we sit with him at his right hand. It helps us understand what our adoption means for us in that there is a mutual indwelling without loss of personal identity. Because of Jesus we are one with the Father and the Holy Spirit and all that I do (play, work, create) and all that I am (a woman, wife, mother, friend) becomes my arena for participating in the Trinitarian life of God. Tell me that this is not wild?

All that I do and all that I am becomes my arena for participating in the Trinitarian life of God.

I can’t dance with my husband in the sweet song of the Trinity unless I rise up and join him on the floor. I have to bring my body to him and allow him to move with me fully independent, unique, but intertwined in a rhythm that must be interpreted apart from the other, yet connected in symmetry.

If I fail to step onto the dance floor, or merely mirror my husband’s moves, I will not be sufficiently distinct to offer him the fullness of who I am. Nor will I be able to join the wild dance of the kingdom.

At our dear friends Nate and Abby’s wedding we threw ourselves into the percussive movement of music we didn’t know with people decades younger and older than us. We danced until our bodies screamed “take me home!” Sweaty, exhausted, and alive we held hands and walked to our car to the sounds of the celebration of love and the joy of the Trinity.

Come join the dance around the crib of the newborn King. Join the throng and dance with every move that is uniquely yours. There is no shame in being you. You are meant to shine and the King invites you to dance with wild abandon and joy.